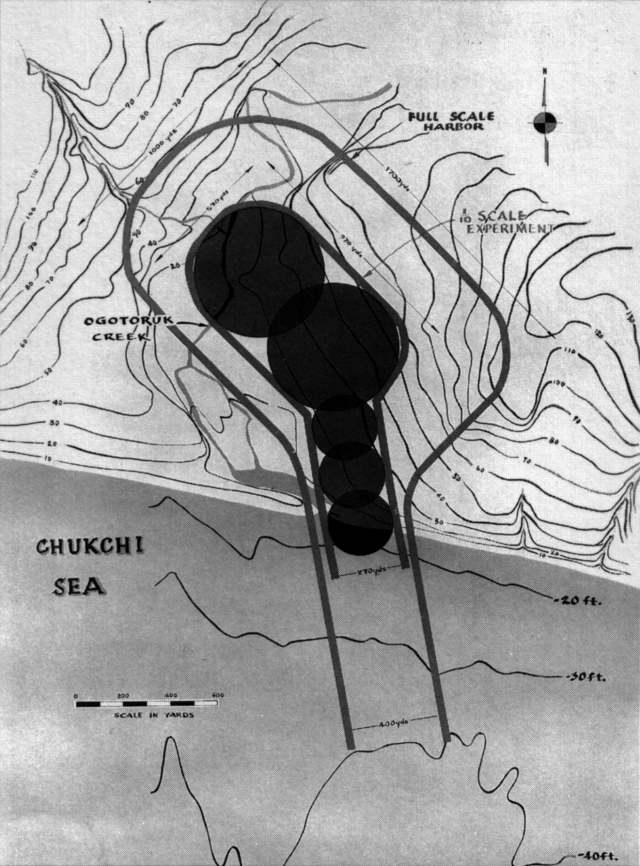

There is a brief and tantalizing mention of nuclear testing off Alaska in Lee Alverson’s wonderful memoir, Race to the Sea, where he writes that he and the R/V John N. Cobb were involved in study around a nuclear project in Alaska. We are extremely grateful to Bob Hitz, in his last post, for making this connection very clear: the Cobb was ordered to conduct research in the Chukchi Sea in the wake of Project Chariot, a controversial plan to use six atom bombs to create a new harbor in Alaska.

Project Chariot is one of those Cold War schemes that makes you think it is fiction. There are many creditable links on the web, so we won’t recount the basics here. But we will say the event played a pivotal role in Alaskan history: the empowerment of remote villages and their people, who mobilized against a plan they had not been consulted it about. It’s a shameful event in the history of University of Alaska, which sought to censor its own scientists.

But beyond all of these connections, Bob tells us something important about the way that science is done. Historians like to talk about the “invisible hands” that aid scientists, the technicians who do the underlying work that makes scientific advances possible. If you’re interested in more, here’s a link to the classic paper on the topic, “The Invisible Technician,” by Stephen Shapin, published in American Scientist, Vol. 77, November-December, 1989. In it, Shapin examines the relationship between the 17th century British scientist Robert Boyle, and the technicians who assisted him in creating the objects he needed to do his chemical experiments.

With his post, Bob has uncovered another facet of invisible technicians, the platforms on which the science is done–namely boats like the Cobb. It joins other great vessels of oceanographic research–perhaps most famously the Challenger, with its three-year voyage around the world between 1872 and 1875. Closer to home is the Albatross, the vessel of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which made the early research cruises off the West Coast at the turn of the century and discovered our poster fish, Pacific Ocean Perch.

One of the consequences of Project Chariot was the recognition of the need for basic research on the Chukchi Sea. This is probably one of the very first research cruises off Alaska; we have explored this topic before and we hope to return to it again.

The year 1959 was a pivotal one for West Coast fisheries. It was the year Soviet processing vessels showed up in Alaskan waters, targeting Pacific Ocean Perch. The ships were off Oregon by 1965 and within three years, the Perch were gone and fishermen like George Moskovita had to find new ways to make a living. Soviet fisheries were far more developed than American fisheries, and the same could be said of Soviet oceanographic science.

History is a web of knowledge. Each strand adds to our understanding. The Cobb made a lot of anonymous voyages, an “invisible” platform, adding to our growing understanding of the sea. Recapturing this particular voyage enlarges our understanding of how science is done, why it is done, and why it is important.

Pingback: Carmel Finley on Cold War Fisheries | The Devil of History